Can you imagine if the length of what you were reading wasn’t measured in pages, but in kilometres?

Specifically over 5 of them?

One woman would go on to do just that; and make one of the most amazing discoveries in the history of astrophysics. Susan Jocelyn Bell Burnell was born on July 15, 1943, on the Northern Island. She grew up in a country home with her family. Since she was a girl, the local school didn’t allow her to study topics interesting to her, such as astronomy. Luckily her family supported her to pursue physics and managed to convince the school to teach her so. Sadly, being underestimated and overlooked would be a problem that she would have to experience throughout her career. She reported in a lecture to Stony Brooke University that she was the only woman in her class with 59 men. “It was the tradition in Glasgow that whenever a woman entered the lecture theatre, all the guys would whistle and stamp and catcall.”

By 1967, Jocelyn was a postgraduate student at Cambridge with her mentor, Antony Hewish. This was following work on quasars, which had been discovered in the late 1950s, a discovery she had helped to pen. She later recalled checking her chart recorder paper and noticing “a bit of scruff” being recorded among the stars. For three months after the initial recordings, Burnell scrutinised the over five-kilometre-long charts and discovered something incredible.

The charts showed that this signal was pulsing, with a regularity of around one pulse every 1½ minutes. The signal was temporarily dubbed ‘Little Green Man 1.’ Jocelyn had just discovered the first recorded pulsar.

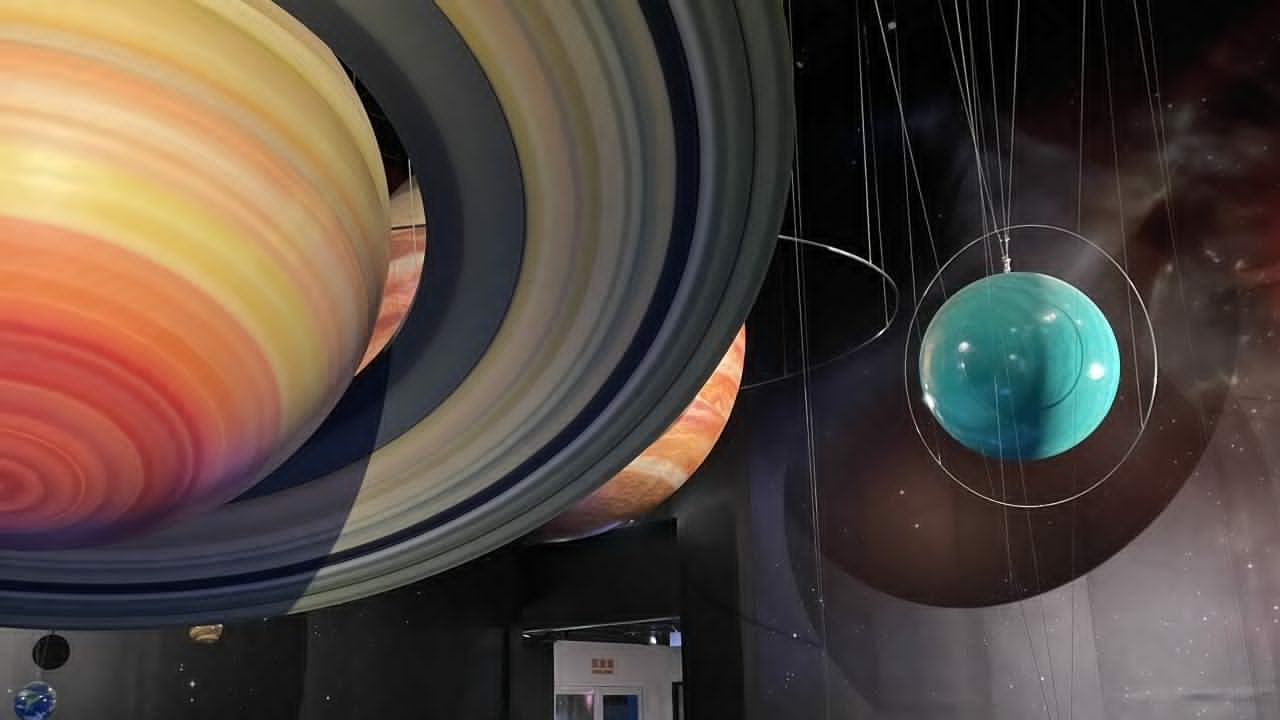

Pulsars are rotating neutron stars that are constantly sending out pulses of radiation. The discovery of a pulsar’s radiation pulses led astrophysicists to discover the existence of neutron stars the very same year. The revolutionary discovery earned the 1974 Nobel Prize in physics, but Burnell never saw it. The honour was awarded to Antony Hewish and astronomer Martin Ryle, without any mention of Burnell or her work.

There was intense criticism of the committee's decision to omit Burnell from the Nobel Prize. Fellow astronomer, Sir Fred Hoyle, accused Hewish of stealing Jocelyn’s work. Although this accusation left Hoyle facing a libel suit Jocelyn initially stated that she understood why the award was not given to her. "I believe it would demean Nobel Prizes if they were awarded to research students, except in very exceptional cases, and I do not believe this is one of them.” However, she later said, “The fact that I was a graduate student and a woman, together, demoted my standing in terms of receiving a Nobel prize.”

She was awarded a damehood in 1999, 32 years after she first saw the “bit of scruff” on the chart recorder and 24 years after the Nobel Prize was awarded to her male mentor and not to her. Although she has been publicly recognised for the discovery in the present day, the Nobel Prize Organisation has not put her as an official recipient of the prize, the whole matter sparking a debate that has had both sides argued right up until this very moment in time and shall likely continue to be discussed for many years to come.

Come 2018 she was awarded the Special Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics. This was both for her work on the Interplanetary Scintillation Array as well as her work discovering pulsars. The award came with a monetary prize of $3,000,000. She decided to donate the money "to fund women, under-represented ethnic minorities and refugee students to become physics researchers".

In 2022 she was put on the £50 notes when an Irish/UK bank was doing a science theme. She was featured among other women who had made important progress in their respective scientific fields.

Sadly the problems that impacted Jocelyn Bell Burnell are still very prevalent in modern society. Women and other under-represented groups still struggle to receive recognition for a lot of their research and achievements, especially those in science. Even today, when I ask people if they know who Jocelyn Bell Burnell is, not one of the people that I asked did. Some of them even had science degrees, and were studying astrophysics!

The story of Jocelyn Bell Burnell highlights the sexism that has spread throughout society and continues to remain at large. Jocelyn deserves to have more widespread knowledge about her and her amazing work on pulsars. If we spread knowledge of Jocelyn around, who knows how many young women and other under-represented groups it might inspire to see science as a worthy career? And who knows how much it might benefit the world?